Cheddar: It's The Star Of The Show

Cheddar is so familiar it feels like it’s been with us since the dawn of time. But it’s not quite that old.

Hard cheese making is thought to have come to Britain with the Romans, and later on the advent of large estates in the medieval feudal system provided enough milk for large cheeses, but you have to wait a bit for something that might have been like cheddar as we know it.

The key process in making this cheese involves the maker waiting for the milk to start solidifying into curd snd then cutting it into large brick-like blocks. These are stacked up at the side of the vat where the whey seeps out and they slowly stick together. This process - cut into blocks, stack, drain, wait - is repeated several times before the whole lot is ‘milled’ or broken up into tiny pieces. This has come to be known as ‘cheddaring’, and you have to get to the eighteenth century before there’s any record of this process - used in all proper cheddar.

The fact that the name of a small village at the foot of the Mendips was borrowed to name the technique has forever linked this cheese to our region, and that area - with its lush pasture and natural caves for maturing - is still a great cheesemaking area today.

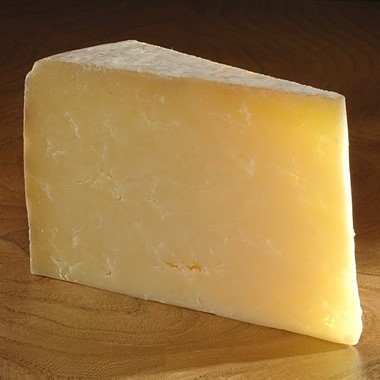

In modern times the name cheddar ‘escaped’ from the Westcountry and cheeses under this name are produced across the world. But most of them - produced in large cheese factories - have little in common with real cheddar as we know it in The Cheese Shed. That’s partly because the ‘cheddaring’ process (very much a hands-on technique) is missed out, or only approximated in some mechanised form. But maturing will be different too. Traditionally cheddar - in 50lb truckles - is wrapped in cloth, then brushed with lard. One writer describes this method - which regulates the amount of air getting to, and the moisture lost by, the cheese as “an evolutionary accident that can’t be improved upon”. Those cloth-wrapped cheeses will sit on wooden shelves in the open air for up to two years. Factory cheeses - plastic-wrapped and maturing much faster - are never going to be the same, and they’re not.

We stock cheddars from four great Westcountry makers, three from Somerset plus Quicke’s - from just north of Exeter in Devon.

Montgomery’s

On a grey and rather uninspiring February day I rounded the slopes of the iron age Cadbury Castle and turned into the yard at Manor Farm, where I met Jamie in the farm office. He explained that his grandfather had arrived in 1911 to find they were already making cheese, about which he became quite enthusiastic. This enthusiasm was passed on to Jamie's mother, and - in due course - to him.

I was keen to know how their present day star status had been achieved. Jamie took me back to the late 80s/early 90s when prospects looked bleak. There was little interest in what we now call 'artisan' cheese; conventional wisdom decreed - not unreasonably - that supplying the supermarkets was the only route to survival. A brief contract with Tesco ended when they de-listed the cheese without taking the trouble to tell Jamie, who only found out when the pallet of cheese he'd prepared for them wasn't collected (Tesco, ruthless? I refuse to believe it). Unsurprisingly, he decided that there was no future in that direction.

But a series of events in the later 90s proved pivotal. First came the double Gold Medals for Best Cheddar and Best Traditional British Cheese at the 1996 British Cheese Awards; this was followed in '97 by a BBC Food And Drink programme ("the phone rang non-stop for days"). Then there was the Great Cheese Theft. This potential nightmare - thieves broke into their store and took £35K worth of cheese - turned into a publicity bonanza for Jamie: journalists loved the story of the heist targeting "the best cheddar in the world". Soon, he started to notice that the press were speaking about 'Montgomery's Cheddar' with no need for further explanation. In other words, they'd arrived.

The Montgomery approach is about rigorous attention to detail and an absolute refusal to compromise in pursuit of the very best. This involves a set of core principles (unpasteurised milk from their own herd, animal rennet, very special starter bacteria, cloth binding, maturation on wooden shelves etc), but also staying alert to the different needs of every batch. Jamie's very clear that the process should never become fixed, and as if to illustrate this, he breaks off to discuss the day's batch with two of his makers, which is taking its time developing the necessary acidity. The point is that every batch is different; the makers need to stay alive to this, making tiny adjustments to the process as needed

Keen’s

Walking through the big maturing room, packed from floor to ceiling with 25 kilo cheeses, it's hard to believe that 30 years ago the Keen family might have thrown in the towel. Pasteurised factory cheese was on every side... “no one's making unpasteurised cheddar any more" seemed to be the consensus... and the options seemed to be either give in (and pasteurise)... or give up.

The family had been making cheese at Moorhayes Farm near Wincanton since 1899, so this was a truly depressing prospect. But then, brothers George and Stephen met Randolph Hodgson of Neal's Yard Dairy. Hodgson (a key figure, along with James Aldridge) in the artisan cheese revival, encouraged them to identify what was unique about their product, and to have faith in it. In retrospect, this advice was spot on. What they needed to do was let the public know about Keen's Cheddar and its distinctive qualities. The problem was that people just thought that cheddar was, well, just cheddar. There was an educational job to be done.

Out of this grew the idea for the Slow Food Presidium for Artisan Somerset Cheddar. Slow Food - originally from Italy - is the international movement dedicated to the pleasures of food and the authenticity of the best artisan produce. Slow Food brings together gastronomy, green thinking, biodiversity and politics, but preservation of traditional foods is at its core. A 'Presidium' identifies and protects the key techniques involved in an important artisan product - in this case, the ultra-traditional cheddar made by just three Somerset dairies: Keen's, Westcombe and Montgomery's.

So what makes Artisan Somerset Cheddar different? Well, it has to be made in Somerset, with unpasteurised (or 'raw') milk from the farm's own cows. The cheese is made in open vats, using traditional starters (the bacteria which start the milk's transformation) are used, and calf rennet. Then, the 'cheddaring' process itself has to be used. You can see James Keen doing this in the photo: stacking the curd in blocks, turning, cutting and re-stacking - this is key to the cheese's eventual texture. Finally, the cheeses are cloth bound and matured on wooden shelves for at least 11 months.

Today George and Stephen have been joined by their sons (Nicholas and James respectively). The ethos at Moorhayes Farm is simple: "We just make cheddar how our grandparents made it”.

Westcombe Dairy

Westcombe Dairy draws on the milk of three farms run by Richard Calver. Richard started cheesemaking in the 1990s - although cheese has been made on the Westcombe site since the 1880s - and got together with fellow makers Keen's and Montgomery's in 2002 to form what the Slow Food movement calls a Presidium, devoted to protecting traditional artisan foods, in this case Somerset cheddar.

Traditional in this case means that unpasteurised milk is used, and must come from the maker's own farm; animal - not vegetarian - rennet is used; the cheddaring process is done by hand; cheeses are then clothbound and matured for at least a year. In addition to Westcombe Cheddar, they also make Westcombe Red, and have taken over the Duckett's cheeses (Duckett's Caerphilly, Wedmore, Smoked Wedmore) since the death of Chris Duckett.

Today cheesemaking is in the capable hands of Richard's son Tom. Tom spent a number of years working for Randolph Hodgson at Neal's Yard Dairy before coming back to look after the marketing of their cheeses: he's now taken over the making itself.

Quicke’s

Quicke's cheese definitely counts as 'artisan', i.e hand-made, but in terms of the people we deal with, they're also one of the larger concerns, with up to 400 tons of cheddar being made each year, and a staff of around ten. The first time I looked into their biggest cheese store was quite a jaw-dropping moment, row after row of huge racks with hundreds of huge 15 kilo chedars slowly maturing. Quite a sight!

When Sir John Quicke and his wife Prue started making cheddar in the early 70s, really traditional cheese making in this country was perhaps at its lowest ebb. The Quickes instinctively went for the old methods and cloth-wrapped truckles rather than the rindless blocks emerging from big industrial creameries, with a 500-strong dairy herd providing the milk.

Today the firm is under the leadership of John and Prue's daughter Mary, whose focus is on the business of making 'world class cheese'. In The Cheese Shed we stock her 18 month old Extra Mature Cheddar, 2 year Vintage and Oak-Smoked Cheddar, as well as Double Devonshire and a very nice firm goat's cheese. In addition there's a Red Leicester and an interesting elderflower flavoured cheddar.