Power Trio: Three Beautiful Strong Cheeses

Our big, bold three

Today the spotight is on three beautiful strong cheeses. But ... hang on. Hold it! Straight away I feel I need to say that just as bigger is not always better, 'stronger' - at least in the sense of that sharp quality we all recognise in mature cheese, isn't the be-all and end-all either. It's just one dimension of flavour. So what we're not highlighting here is any sort of 'vindaloo' cheese. It's more about strength of character, complexity and fullness.

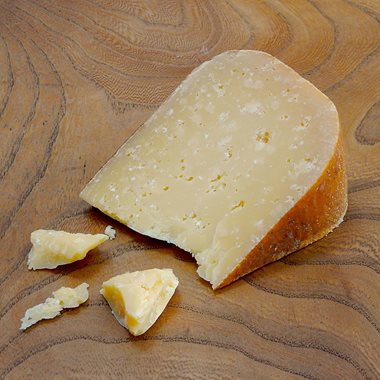

Anyway ... here in The Cheese Shed we're partial to big flavour experiences, and recently we've got our hands on longer-matured versions of three favourites. Cornish Gouda - in the version we normally get - is six months old. However, maker Giel also keeps some for two years! As you might imagine, Extra Mature Cornish Gouda is a very different beast, going somewhere in the direction of parmesan. You'll be struck by the texture - granular and with prominent crystals.

We also have some Extra Mature Beenleigh Blue. Now, I don't think regular blue cheeses tend to be marured for that long - normal Beenleigh, for example is ready in four months. This is probably because the blue peniciilium roquefortii bacteria don't need terribly long to do their work - and it's the blueness which is the cheese's main feature. Here, however, Ben Harris has kept some for 12 months. We tried some alongside the younger version and, to be honest, each has its own appeal (the younger being lighter, fresher, more lemony). But the new one's great if you like your blue to pack a punch. Try some!

The trio is completed by one we've had for some time now, the two-year old Quicke's Vintage Cheddar. Mary Quicke selects just a few 18-month cheeses to be kept on the shelves for that bit longer; the result is something that I regularly rave about.

What happens to cheese as it matures?

At the very beginning of the cheese-making process, starter bacteria are added to the milk. What this does is start souring the milk - it's the conversion of its natural sugars, or lactose. into lactic acid. Simply, the longer you keep cheese, the further this process goes. The bacteria are multiplying and eating more and more of the lactose, making more lactic acid. Result: the cheese gets 'sharper' or 'stronger'.

Then there's something else going on. As well as starter bacteria, cheesemakers add something to curdle or clot the milk - sometimes that's rennet, sometimes a non-animal alternative. Whichever way it's done, the result is long protein chains which - with time - break down into smaller amino acid compounds, and what they do is create a whole lot of different flavours. The process - called proteolysis - also sometimes leads to the tyrosine crystals seen, for example, in this Extra Mature Cornish Gouda.